What a Day at Work Consists of for a Forestry Planning Summer Student

July 16, 2018 3:23 pm 2 Comments

For those readers that may not be particularly literate in forestry practices and jargon, I thought I’d take a moment to fully explain what it is I do on a daily basis.

The main task myself and my current bush partner Doug have been assigned with is site plan (SP) data collection. At this point in time, the blocks we are working in have been layed out and a cutting permit has typically already been obtained. Our job is to traverse as much of the block as we can to find any abnormalities within the block that may hinder the ability of harvesters or tree-planters to carry out their jobs. These abnormalities include unfavourable soil substrates such as clayey or sandy substrate, water receiving areas containing high soil moisture, signs of endangered wildlife, and riparian areas that have evaded the mapping ability of LIDAR coverage.

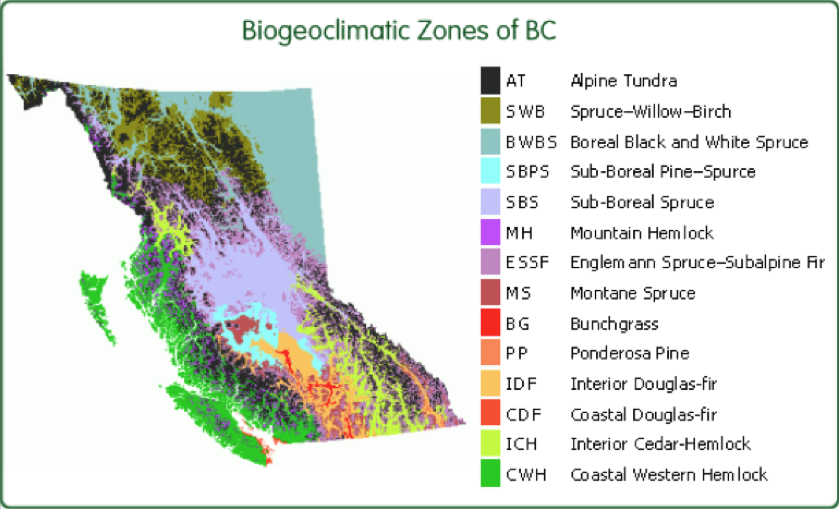

As we walk through the block, we are constantly scanning the forest floor and canopy for changes in vegetation that may indicate a change in site series. A site series is the most specific tier used in the Biogeoclimatic classification system utilised here in BC that divides the province into 14 BEC zones which are further divided into subzones, variants, and site series. The majority of the work we do takes place in the SBS (Sub-boreal spruce zone) or the ESSF (Engelmann spruce subalpine-fir zone). We are given maps that show us the BEC zone, subzone, and variant that we are working in but it is our duty to determine where changes in site series occur. When a change occurs, it typically indicates a change in soil nutrients, soil moisture availability, elevation, or slope gradient and aspect.

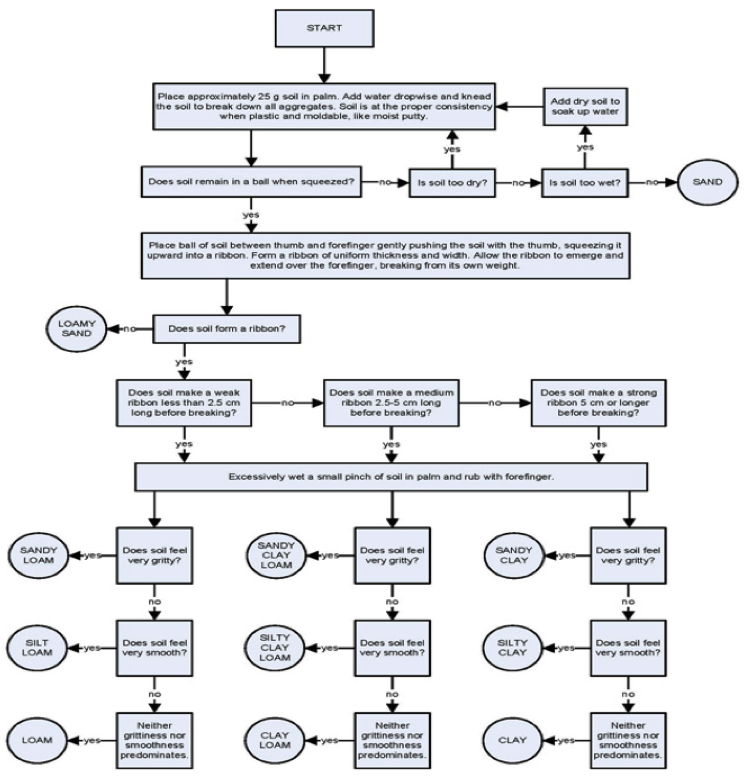

To determine soil texture and the depth to unfavourable soil substrate, pits are dug ranging in depth from 35-65 cm. The frequency of these soil pits varies depending on the amount of variability within the block. In a homogeneously vegetated block, we may only do about 6 soil pits in a 200 hectare area. Soil horizons are classified, measured, and textured to determine the approximate percentages of clay, silt, and sand present. Soil texturing involves wetting a soil sample from each horizon and ensuring there are no roots or coarse fragments left in the substrate. Numerous tests may be performed but generally speaking sand will feel gritty, silt will feel soapy and smooth, and clay will feel sticky. A combination of these textures in a single sample is considered a loamy soil. The humic layer (the organic component of soil, formed by the decomposition of leaves and other plant material by soil microorganisms that occurs above the mineral soil) is then measured. The percentage of the soil comprised of coarse fragments (any soil particle greater than 2 mm in diameter) is also approximated to the best of our ability.

At each soil pit, we are required to fill out an “SP Report card” which incorporates sections for block information, topographical features, vegetation type and cover, soil characteristics, and a hazard key. Once the card is filled out, a key is used to determine the site series. The hazard keys are filled out back in the office where the lack of insects provides a more peaceful working environment. The hazard keys are broken up into 5 different sections including forest floor displacement, erosion, mass wasting, and soil compaction. The hazards in each section range from low to very high depending on slope gradients, soil texture, moisture content, and coarse fragment content and the depths at which these occur. For example, if a soil is found to have clayey substrate commencing just below the humic layer, the soil compaction hazard will immediately jump to very high due to the lack of macropores within clay soils. If these soils are compacted further by the use of heavy machinery, it will be even more difficult for roots and water to penetrate the soil which will create problems for replanting. In such blocks, winter harvesting is often advised to minimize these potential predicaments.

As we walk through the block, we are also on the lookout for practically anything we deem noteworthy. These may include areas of high deciduous tree cover that is undesireable to foresters which, as a result, may be left as a Wildlife tree patch. Small unrepresentative patches of high moisture indicative vegetation, steep slope gradients, sparse canopy cover, blowdown, signs of beetle attack are also example of notes we have taken in the field. Streams are typically already mapped but may not always occur in the same location mapped out by the LIDAR coverage. If we come across a stream that has not been mapped or previously traversed and classified, we must complete these tasks. The stream must be flagged and GPS’ed and a stream traverse, in which the bank depths and widths, the presence or absence of scour, and any fish passage barriers are noted to determine the stream classification. Fish passage barriers include steep slope gradients and waterfalls. Biologists are often called upon to ensure the presence or absence of fish. Stream classes range from S1-S6; S1-S4 being fish-bearing. If there is no continuous scour (evidence of objects being transported downstream by flowing water such as rocky creek beds) over 100 meters in length, the riparian area is classified as a non-classified drainage system (NCD).

Once all the field work has been completed, an office day usually follows where we compile all our information and notes and write a Site Plan report for the block or blocks of interest. Any GPS tracks are converted to shapefiles and digitized onto ARCMap. Hard copies of the SP reports, maps, and SP cards are placed into folders before we submit them to the respective planning forester.

Anyways enough of the mundane details of my daily work routine. On a completely different topic I have made good use of my weekends recently and have visited Bowron lakes, Farwell Canyon, and Tatlayoko lake. I will most likely dedicate a future blog post to one of these epic adventures.

I have always loved wildlife and have been keeping tabs on my findings throughout the summer. So far, my summer bear and moose counts are at 52 black bears and 18 moose. Other noteworthy sightings have included a lynx, caribou, pelicans, and sandhill cranes. The grizzly bears unfortunately continue to evade me despite multiple sightings from other summer students.

That’s all for now! I will attempt to put together a video of a day at work for my next blog post. Another blog post of one of my weekend excursions is also forecasted for the near future. Thanks for the read!

Alexander

2 Comments

Already looking forward to reading the next one Alex!!!

Good stuff Alex!