School…on steroids

17 juin 2016 9:40 Laisser vos pensées

François Lake, British Columbia

Today marks a month working here at Northwood. It is also the day I realized hey yunno what? I think I can actually do this whole work thing. In fact I might actually like it better than school. The staff here at Northwood has been extremely welcoming, from showing me around different parts of the mill to the entertaining lunch room conversations.

In the beginning however I really wasn’t sure I could do this. The four day work weeks are awesome! But initially, after a ten hour shift I was downright exhausted. My parents and friends had warned me about this, but I didn’t quite believe them. It couldn’t be that different to school, right? Wrong.

It feels like school….school on steroids.

In school we are taught the theory and the correct applications. But in the field, equipment rarely functions as it’s supposed to. It’s incredible the amount I’ve been able to learn from the team here at Northwood as they resolve daily issues associated with running a pulp mill. This is something you don’t particularly learn about in school.

This makes me think back to something I heard at an APEGBC event my first year at UNBC:

Learning is a lifelong process.

I remember being a little apprehensive about this. I had barely completed a year of my engineering degree at the time and was already feeling overwhelmed. The idea of constantly being under that amount of stress was not an appealing one. As the degree progressed and we gained a more extensive background of engineering practices things started to get more interesting. I even learnt how to better balance the stress of school. I found myself progressively getting curious about certain aspects, some of which I have already used in my work here at Northwood. Some of the projects I am currently working on included looking at the correlation between hog moisture and boiler efficiencies, pump energy savings associated with motor sizing, an air leaks survey and analyzing tariff supplements. It’s funny because I didn’t particularly enjoy learning about some of these in school, however here, when you can see their exact application it’s significantly more appealing.

When asked to do the air leaks survey a couple weeks back, I was definitely anxious. This would be my first time in the mill alone. The night before I was to do the survey I was on the phone with my dad and expressed my nervousness. My dad has been working as a Millwright for the past 35 years so I was hoping he could offer some advice. He told me not to worry, to use common sense and what I was taught during my safety orientation. This did nothing to ease the nerves. Wasn’t this advice obvious? Yet it was this advice I clung on to as I walked around the mill Monday morning (Thanks Dad!!). I started off in one of the digesters. Once I got over the mental block I started to realize how interesting the digesting process really is.

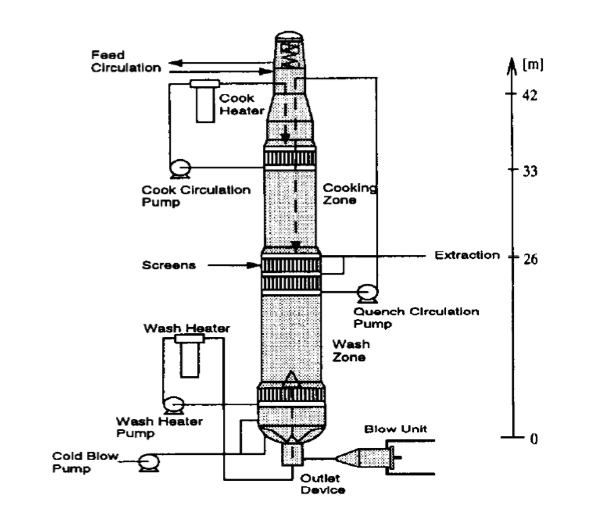

A Kamyr steam/liquor phase digester for continuous kraft cooking and the horizontal axis in the profile plots

Each digester is like a large pressure cooker, rising eight stories high with a conventional cooking of about 1,000ADt/day. Northwood’s chip supply comes primarily from residual sawmill wood. The chips are screened on four screening lines, with the accepts going to the pins feeder and the rejects used as hog fuel. The pins feeder is basically used to proportion the chips to the appropriate digester. Before entering the digester the wood chips are approximately 50% water, 25% cellulose fiber and 25% lignin. Lignin is the natural “glue” that holds the wood fibers together. In the digester alkali, which is also known as white liquor is added to defibrate the wood chips. The liquor chemically reacts with steam to remove the lignin between the wood fibers. This delignified mass is what we call pulp. The free liquor along with the dissolved lignin is called black liquor.

Recently during a shutdown, my supervisor Teddy took me inside one of the two Recovery boilers here at Northwood. I get claustrophobic in confined spaces so I was a little worried. To my surprise the recovery boiler was massive with a 35ft2 base rising 124ft high. As we walked on the scaffolding built around the inside of the boiler, Teddy explained how Recovery Boilers work. The diluted black liquor from the digester is concentrated by evaporating the water out. The lignin and remaining cooking chemicals are left behind which are burned in the recovery boilers. Black liquor is burned to generate steam and electricity for the mill. Once burned, all that’s left of the black liquor is green liquor which is basically the spent cooking chemicals. Lime is added to the green liquor to recycle it back to the original chemical composition of white liquor. The recycling of liquor is known as the Kraft process and can be used again and again making the process not only cost effective but also sustainable.

References

Finn, Michelsen A., and Foss A. Bjarne. « A Comprehensive Mechanistic Model of a Continuous

Kamyr Digester. » Science Direct 20.7 (1996): 523-33. Web. 13 June 2016.

IdForestProducts. « The Making of Pulp. » YouTube. The Idaho Forest Products Commission, 19 Oct. 2012. Web. 13 June 2016.