A Ducky Week on the River

June 23, 2017 7:34 pm 1 Comment

Today I have a special experience to share! In mid-May, I had the pleasure of participating in a Harlequin Duck capture program for three days. I have so much to share so I’m just going to dive in!

Harlequin Ducks (scientific name Histrionicus histrionicus)are a migratory species of duck that nest in the tributaries of high elevation streams and rivers. Female Harlequins return to their natal stream (where they were born) to nest, and they typically mate for life. Pairing up occurs in coastal regions, where they spend the majority of their lives.

One of our local mines is home to a breeding population of Harlequins that inhabit a river which flows through the mines property. The mine has been working with a local wildlife research company, Bighorn Wildlife Technologies, in monitoring the population to find out if and how the mining operation is affecting the success of the population. This study has been going on since 1986, led by an incredible biologist named Beth. One thing that really stands out to me is how collaborative this project is, even internationally; you’ll see that demonstrated a lot throughout this post!

Although this project isn’t a West Fraser project, Hinton Wood Products is actually a “funder” of the study in the sense that they acquired forestry-specific research money for Beth from an association called FRIAA. The money comes from our stumpage fees in Alberta, is only available to forest product companies and must be applied for. I was able to get involved because Laura (my supervisor) thought it would be a great opportunity for me to meet other biologists and learn about the birds as well as the mine.

My role was to work on the small crew to set up nets, capture ducks, and help process the ducks (take measurements, collect information, and apply identification bands).

The process for capturing the ducks is actually quite simple. We use fine, soft netting, called a mist net, which is specially designed for capturing birds. The concept with a mist net is that the birds can’t see it because the line is so small. The net we used was sized specifically to small ducks, and was also 18m in length (length selected for the width of the river).

Image 3. A fully set up net! It’s pretty challenging to see the netting itself, but you can see how we use a three point anchoring system.

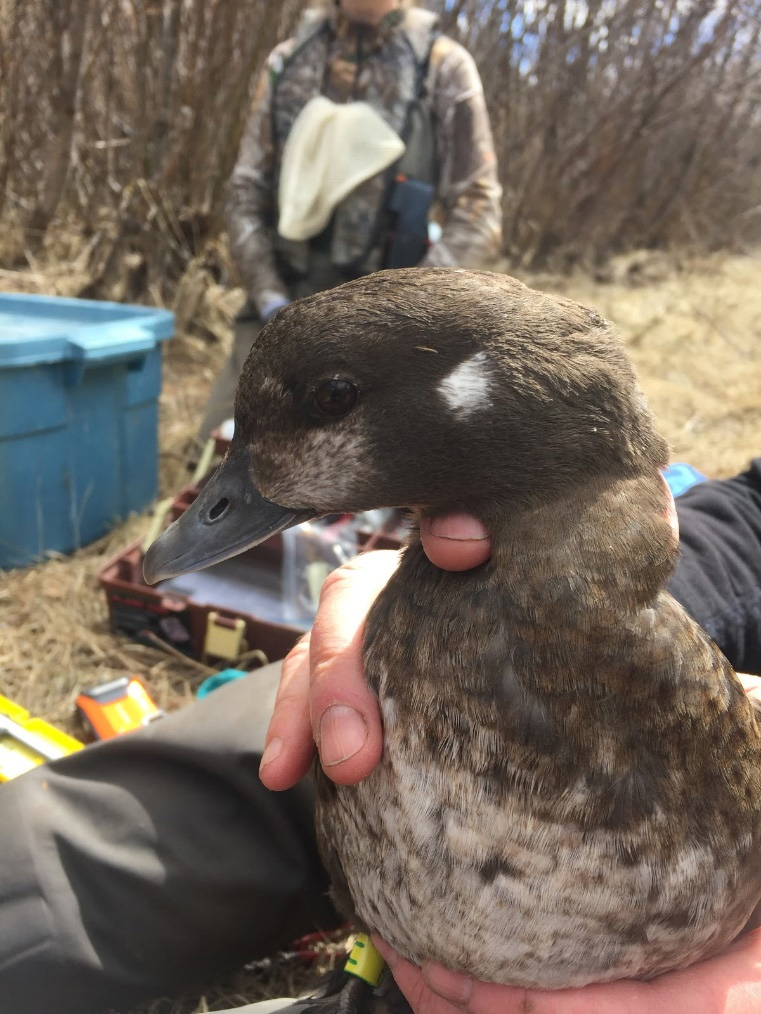

So how do we get the ducks into the net? Once we have spotted a pair of ducks on the river, we set the nets up a ways downstream, and we hide in camouflage along the river bank. Then, one member of the crew walks down the river and encourages the birds to fly towards the net, where they get caught and we hurry out to untangle the birds. This system works well for Harlequins because they tend to fly very low to water, and generally don’t fly high enough to miss the net. From there, we place them in soft, mesh sacs and cover them in a towel so they remain calm. We bring them to shore and begin processing them.

This year, a veterinarian and her summer student joined in the captures to take blood and feather samples. The blood samples are being sent to a laboratory in Washington for some genetic sampling and will be used by another research team in Maine to detect heavy metals, specifically mercury. The feathers are going all the way to Alaska for stable isotope sampling, which can provide information on the diet of the birds and be traced back to the locations in North America that they have been! This is incredibly neat technology for understanding where migratory birds go and what they do while they are away.

Image 6. I love this image because it really captures the behaviour of the ducks. They were so gentle and curious on shore with us. You can see how lightly Beth is holding her and there is no struggle.

Image 8. A geolocator on a female’s identification band. They were attached onto the band with a tiny zip-tie. This geolocator was clipped onto her band last capture season, and therefore has an entire year of information logged on it. We clipped off the old band with the geolocator and re-banded her with the same number.

Geolocators work by measuring light and darkness (photo-period) to determine day length. This can provide information about her location, as the day length varies seasonally and by location. Geolocators also allow us to tell when she is sitting on her eggs (signified by a long consistent dark period), and how long she does this for.

Image 9. Documenting the plumage and its condition with pictures is an important part of the data collection. Did you notice the satellite antenna?

The satellite transmitter on the males is a small implant with a fine, 6-ish inch antenna positioned off the back of the tail. This device tracks the movements of the duck in real time. Using a software system back in the office, Beth can watch where the ducks are year round, and see exactly when they come back to river, and where about on the river they are. If that isn’t neat enough, the main focus of the transmitters is actually to collect information pertaining to migrations patterns, molt locations (where the males shed their feathers in the late summer), and winter range locations. These antennas give us incredibly accurate and specific information that we would not get with any other technologies. The transmitter project was an initiative last year between Alberta, Montana, Wyoming, and Washington (males in all these area were equipped with these devices).

After we have processed both birds in the breeding pair, we release them together in order to minimize stress and make sure they don’t lose each other! This was a super fun task. I loved feeling how powerful their little legs were pushing off my hands, and seeing the two lovers fly away together waspretty rewarding after a job well done.

Image 11. The best part of the day! Releasing a breeding pair of ducks with the vet student (myself in the foreground, and her in the background).

Image 12. A close up us preparing to release the last day of captures. Pictured here (from left) is myself, my supervisor, and a field tech/GIS analyst from Bighorn Wildlife Technologies.

This study is one of a kind in the world. There is no other Harlequin program that has been ongoing for this long at such a high level of detail. I feel incredibly fortunate to be a witness to this study and to have participated in this year’s data collection, and I can’t thank Beth, Laura, and the rest of the team enough for providing me the opportunity.

On a final note, I want to express how the Harlequin Duck Study is a fantastic example of industry participating in biological research. This type of research is critical in developing real management strategies that play out on the ground to benefit all aspects of environmental sustainability (in this case, helping to ensure the success of these amazing birds). I hope you enjoyed this quick glimpse into this world of industry research; be sure to keep your eyes open for the many examples of it around you!

Thanks for stopping by!

Syd

1 Comment

Another great post Sydney, keep up the good work!